Dracula has Risen from the Grave

Dracula has Risen from the Grave - Released Feb 6, 1969 USA (Nov 7, 1968 in UK). Directed by Freddie Francis

This Dracula franchise effort from Hammer Films has Christopher Lee back under the cloak and wreaking mayhem at familiar Pinewood Studios, with Veronica Carlson the main target and Freddie Francis directing.

The story in Dracula has Risen from the Grave has the irony of atheist Paul (Veronica Carlson's boyfriend in the tale played by Barry Andrews) and the Monsignor (played by Rupert Davies, who brings on Dracula's vow of revenge because he has blocked the entrance to his castle with an enormous crucifix) brought together from opposite sides of the philosophical tracks in a desperate battle against a dangerous supernatural foe. How does Dracula have these powers? The film (and no characters) asks this question, nor why a crucifix is anathema to the blood-sucker (though within Hollywood vampire movies, it is basic knowledge that a cross is a kind of visual metaphor for Jesus Christ and the command of "get thee behind me, Satan" from scripture, in which a demon, which is what Dracula and his kind apparently are on some level, are subjugated simply by reminding them that they are outranked by humans in the hierarchy of beings as created by God.)

But how is Dracula back in action at all? He gets resurrected by a convenient, and bloody, accident at the place where he was frozen into a body of water at the end of the previous film, Dracula, Prince of Darkness. This causes a problem with the story chronology in Dracula has Risen from the Grave because we hear dialogue that it has been a year with Dracula under the ice (and in another scene a villager says its been just a few months) and yet we begin the tale with a dead girl swinging out dead from the bell in the steeple of the village church with twin wounds in her neck, meanwhile the Count is still, well, down for the count in the frozen waters. Who killed the girl? This preliminary scare is clearly meant to herald that the grip of Dracula's evil is still on the local village (where the frightened, superstitious villagers won't attend Mass because the shadow of Dracula's castle falls upon their church) but it also makes no sense unless (1) this scene is actually meant to be the ending of the previous film released three years before; or (2) there's some other agent of vampirism on the loose since Dracula is occupied elsewhere.

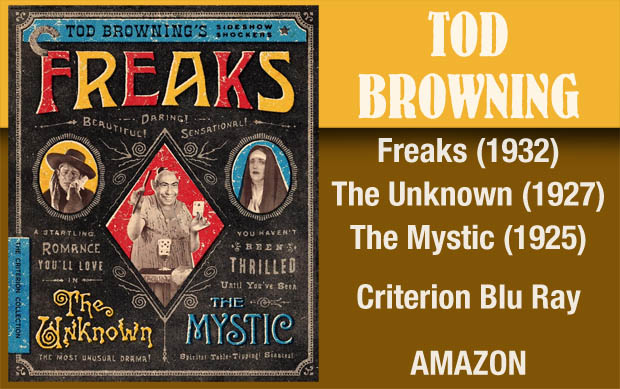

Tod Browning 3 Films – Freaks / The Unknown / The Mystic: Tod Browning’s Sideshow Shockers, Criterion

We also have the simple realization Dracula isn't a dead and decayed body in the frozen liquid (and he certainly isn't in a grave as stated by the film's title) but rather just stuck in the ice, for a year somehow in a place without a spring or summer thaw, patiently waiting for a sequel.

Once the King Vampire is back on his feet, he uses his new henchman, a local priest who is riven with doubt and fear, to find a new coffin (unceremoniously dumping the decaying body of a woman from a just dug up box) because the Count can't get back into his castle and he is going to need a place to stay during the coming daylight hours. This ill treatment of a dead woman is just a precursor to the generally rotten treatment Dracula gives to all his living lady-friends, though in the strange psychology of Dracula movies, an awful lot of them are depicted as appreciating this sort of brutal attention.

Barbara Ewing is on screen from out of Hammer's troops of beer-hall waitresses (as Zena) and she becomes another victim to the Count's appetite. But Zena is only a willing victim until Dracula's eyes fall upon Veronica Carlson, which soon has Zena asking several times the rather reasonable question "What do you need her for? You got me!" a logical query but when up against Dracula's addiction to pretty girls, this only leads to Zena's demise.

Ewan Hooper is the disturbed local priest who hasn't got the faith to take care of business with Dracula and falls under his control. As a priest dealing with the vexing problem of evil, Hooper's characterization is that the priest finds it all rather unpleasant, but once he is employed by Dracula, he likes this even worse and looks perpetually plagued with a sick stomach.

Rupert Davies (as "The Monsignor") is very good and lends the film the sort of authority that a Prof. Van Helsing does in other renditions of Dracula against the Good, though he shares that with Barry Andrews (as Paul, the atheist) who has to pick up the job of fighting the Count when the Monsignor isn't physically up to the task. Their initial meeting goes poorly, with Paul politely but bluntly letting the Monsignor know that he isn't playing on the Monsignor's team:

Paul: I'm an atheist, Sir.

Monsignor: I beg your pardon?

Paul: I'm an atheist, Sir.

Monsigno: You mean you deny the existence of God?

Paul: I don't deny it, I just don't believe it. It's my own opinion, Sir.

Monsignor: You know who I am?

Paul: Yes, Sir.

Monsignor: And you come here to my house, speaking this blasphemy?

Paul: You asked for my beliefs, Sir, and I have given them. It was an honest answer, Sir. You said you liked for people to be honest.

Well, the Monsignor doesn't like this sort of honesty, and has a petulant response which ends with Paul exiting the little dinner party given so that he and the Monsignor (who is the guardian of Veronica Carlson's character) could meet. Paul heads back to the beer hall (or pub, I guess, since all these Germanic characters are actually played by English actors) and gets drunk on Schnapps, something well out of his character as he states shortly after when having a drink of water "it's delicious. I don't know why I drink anything else."

Part of what happens in Dracula has Risen from the Grave is the dilemma of generational clashes of the 1960s, and this is not only represented within the story by the conflict between Paul the atheist and Monsignor the Man of God, but by Paul's curly mod hairstyle of 1968. When Zena looks upon the evidence of infection (on her neck) after her tryst with Dracula in the woods, it seems like a metaphor for a modern STD.

The script by Anthony Hinds contains some interesting mixes of the usual Hollywood vampire lore (something that Hammer films do in general) with more modern considerations, and having Paul's atheism teaming up in one tense scene with the fallen priest's dubious faith results in a near disaster, which is the film compelling the characters with the message you better find some faith, and you better find it fast. Unfortunately, the sections of originality in the film are then plagued by episodic chronology and cliché chase scenes.

Lee is a scary Dracula, half-animalistic monster and the other half a weirdly misogynistic womanizer who is either staring at the ladies with clear brown (and sometimes bloodshot) eyes, and the rest of the time he is slapping them around. This Hammer film is a reflection of the era in which it was made (1968 England) and the standard vampire paradoxes about blood, addiction, sex and religion, get wrapped around each other. As with a standard monster film, the main message seems to be everything can get you killed except love.

Dracula in Dracula has Risen from the Grave will of course be conquered and the young lovers will triumph, but Christopher Lee will bounce back in cape for several more Hammer Dracula films (and a few non-Hammer) and will work through the same set of tropes all over again. Whatever Dracula is trying to achieve, it always is rather short-lived, built upon only a combination of his supernatural power (which looks an awful lot like celebrity charisma) and brutality.

Rupert Davies

What's Recent

- The Devil and Miss Jones - 1941

- Sinners - 2025

- Something for the Boys - 1944

- The Mark of Zorro - 1940

- The Woman They Almost Lynched - 1953

- The Cat Girl - 1957

- El Vampiro - 1957

- Adventures of Hajji Baba – 1954

- Shanghai Express 1932

- Pandora's Box – 1929

- Diary of A Chambermaid - 1946

- The City Without Jews - 1924

- The Long Haul

- Midnight, 1939

- Hercules Against the Moon Men, 1964

- Send Me No Flowers - 1964

- Raymie - 1964.

- The Hangman 1959

- Kiss Me, Deadly - 1955

- Dracula's Daughter - 1936

- Crossing Delancey - 1988

- The Scavengers – 1959

- Mr. Hobbs Takes A Vacation - 1962

- Jackpot – 2024

- Surf Party - 1964

- Cyclotrode X – 1966

Original Page May 18, 2015 | Updated May 26, 2022