Review of Strangers on A Train - 1951

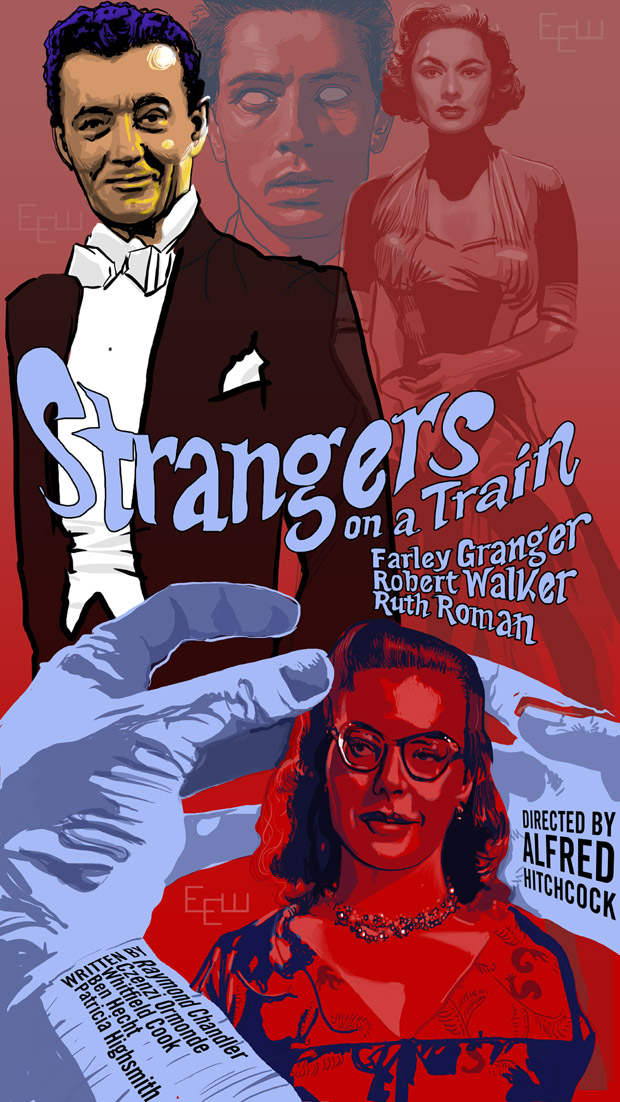

Hitchcock's Strangers on A Train - Released June 27, 1951, directed by Alfred Hitchcock

"I don't talk much, you go ahead and read."

Robert Walker (as Bruno Antony) says this to tennis star Guy (played by Farley Granger) when they meet aboard a train traveling north out of Washington DC's Union Station. Comfortably lounging across from one another, their shoes bump together and their chance meeting turns into the seed of the story running through the rest of Strangers on a Train, that is, Bruno trying to get Guy to fulfill on an odd little bargain made in sincerity by Bruno but only in jest by Guy: that they swap murders of two people that are tormenting them. Right from the start, though, Hitchcock wants us to see a difference in the two men by showing us a difference in their shoe ware: during the opening credits the main object we see are Bruno's flashy "cad" shoes stepping through the ornate train station while Guy's sombre and conservative dark shoes steadily plod along to board the train where they meet.

After their introduction to each other, Bruno's claim he's going to not talk and let Guy read his magazine (which Bruno titters at slyly over Guy's shoulder) shows Bruno is hardly honest about his own behavior, because he is soon talking incessantly. Walker gives the character of Bruno a soft vocal tone that is part communication and another part a cajoling insistence, a narration that shows Bruno thinks that their meeting is almost like predestination, but Guy is only half-way engaged with the conversation after it changes from the subject of his tennis career and then he simply wants to be left alone as what Bruno is saying becomes increasingly crazy.

And what Bruno says becomes what in many Hitchcock movies is a kind of centerpiece, the method of how a murder is carried out. In Strangers on a Train it is "trading murders," Bruno's cagey plan to remove motive and personal connection between the victim and the perpetrator. We learn that Bruno has been pondering the way to succeed with homicide for quite awhile, and in a brief glimpse of his home life we see his motivating problem: his wealthy father trying to convince Bruno's indulgent mother that they must do something about "that boy before it's too late."

For Guy, though, the idea of murder is just an expression of his rage for a moment when he learns that his estranged wife, who is pregnant with some unknown man's baby, has gone from wanting a divorce to now seeing it as a way to keep Guy the tennis-star with important connections for a future political career, fleeced in perpetuity, and on top of that a chance for cruelty since it trashes Guy's romance with a senator's daughter, played by a stately Ruth Roman. Actress Kasey Rogers plays the extra wife and gives the character not only a roving eye but a slyly understated streak of cruelty. In this perverse script (credited to the novel by Patricia Highsmith, screenplay by Raymond Chandler, Whitfield Cook, Czenzi Ormonde) both Guy and Bruno are caught up in romantic triangles, Guy vexed by a wive he unexpectedly cannot get rid of, and Bruno by a father who intrudes upon the lazy playboy lifestyle powered by Bruno's relationship with his mother.

In Rope, Rear Window and Lifeboat, Hitchcock kept the cast (and audience) locked in together using a single physical location where the story takes place. Strangers on a Train doesn't go as far as those films in pursuing tension via claustrophobic visual sameness, but the location of a carnival for a murder early in the film and then the place later used for a confrontation between Guy and Bruno makes the carnival a kind of character in Hitchcock's visual story, a place where humans go to be amused and entertained, a not so subtle likeness to a motion picture audience. This is particularly highlighted by Hitchcock when the particular specific location of a murder at the carnival has become a lucrative and highly sought after destination by ticket buyers.

But Hitchcock doesn't dig too deep into all of this, more interested in letting a smiling (and sometimes smirking) Robert Walker steal most of the scenes he is in. While Farley Granger gives Guy a growing sense of flailing panic as the terms of a murder bargain he doesn't even realize he has made, and which exists mostly in Bruno's head, begins to overwhelm every aspect of his life, Hitchcock provides Guy with a solid ad hoc family to support him, Ruth Roman as the would-be new wife, her father played by Leo G. Carroll, and Patricia Hitchcock as a humorous younger sister.

Besides how carnivals and movies are alike, the other thing on Hitchcock's mind in Strangers on a Train is the one that appears in probably all of his other films, which is that as exotic a place as a carnival is, like the films Nightmare Alley and Freaks also show, two films preoccupied with the world of the carnival (and possible to be seen as a metaphor for society at large), Hitchcock is showing us a world in which murder can happen anywhere that humans congregate.

What's Recent

- Island of Desire - 1951

- Road to Morocco

- The Devil and Miss Jones - 1941

- Sinners - 2025

- Something for the Boys - 1944

- The Mark of Zorro - 1940

- The Woman They Almost Lynched - 1953

- The Cat Girl - 1957

- El Vampiro - 1957

- Adventures of Hajji Baba – 1954

- Shanghai Express 1932

- Pandora's Box – 1929

- Diary of A Chambermaid - 1946

- The City Without Jews - 1924

- The Long Haul

- Midnight, 1939

- Hercules Against the Moon Men, 1964

- Send Me No Flowers - 1964

- Raymie - 1964.

- The Hangman 1959

- Kiss Me, Deadly - 1955

- Dracula's Daughter - 1936

- Crossing Delancey - 1988

- The Scavengers – 1959

- Mr. Hobbs Takes A Vacation - 1962

- Jackpot – 2024

- Surf Party - 1964

- Cyclotrode X – 1966

Original Page April 27, 2016 | Updated September 26, 2022